Class Mammalia

Order Rodentia

Family Sciuridae

Spermophile Ground Squirrels—Spermophile Ground Squirrels // Spermophilus cochisei—Cochise Ground Squirrel // Callospermophilus lateralis—Golden-mantled Ground Squirrel // Ictidomys/Xerospermophilus)—Ictidomys or Xerospermophilus Ground Squirrel // Ictidomys tridecemlineatus—Thirteen-lined Ground Squirrel // Otospermophilus bensoni—Benson Rock Squirrel // Otospermophilus beecheyi—California Ground Squirrel // Otospermophilus variegatus—Rock Squirrel // "Spermophilus" cochisei—Cochise Ground Squirrel // Urocitellus elegans—Wyoming Ground Squirrel // Urocitellus townsendii—Piute Ground Squirrel // Xerospermophilus mohavensis—Mohave Ground Squirrel // Xerospermophilus spilosoma—Spotted Ground Squirrel // Xerospermophilus tereticaudus—Round-tailed Ground Squirrel

Since the naming of the genus Spermophilus by Cuvier in 1825, members of the genus have been split and lumped taxonomically in various ways, with Spermophilus recognized in recent years as consisting of a number of subgenera. In a far-reaching study including both molecular and morphological data, Helgen et al. (2009) have split the genus into eight genera. The restricted genus Spermophilus is limited to Eurasia. Anticipating that this taxonomy will be widely accepted, the system is adopted here. The changes are not without problems for fossil material, however. This is especially problematic in regards to taxa formerly relegated to the subgenus Ictidomys, specifically, S. spilosoma and S. tridecemlineatus. The former species has been transferred to a different genus from the latter, but identifications to subgeneric levels generally have been on the basis of dental characters shared by both.

The taxa listed in the directory header above are taxa in our region that generally have been published under the genus Spermophilus. In many cases, the taxon recorded from the fossil record is identifiable to a currently recognized taxon; in other cases, however, sufficient evidence is not recorded as to allow such—these are listed below as Spermophiles.

Synonyms. Most literature after about 1950 until after the recent publication of Helgen et al. (2009) uses Spermophilus for all of the genera noted above, though occasionally other names, such as Callospermophilus, were used.

Ground squirrels are widespread in both the New World and the Old. They are mostly inhabitants of grasslands or shrublands. Being active during the daylight hours places a premium on being able to spot predators in time to take cover. Activity usually is close to a burrow opening that is a haven from most predators except snakes and certain members of the weasel family (various weasels of appropriate size that are able to enter the burrow and the American Badger that is expert at digging out burrows).

Tamias (chipmunks) and Ammospermophilus (antelope squirrels) have many similarities with the ground squirrels. Dental characteristics generally will separate Tamias (see Sciuridae and Tamias accounts). To repeat from the Ammospermophilus account, the masseteric tubercle is directly below a narrowly oval infraorbital foramen, whereas in taxa formerly assigned to Spermophilus, the masseteric tubercle is medium to large and ventral to slightly lateral to an oval or subtriangular infraorbital foramen (Hall 1981). Other differences are more subtle and most identifications depend on direct comparison with modern specimens.

Literature. Hall 1981; Helgen et al. 2009.

With a number of species possible, including those with considerable overlap in size, many elements that can be identified as a ground squirrel cannot be identified to a lower taxonomic level. Most were identified originally as members of the genus Spermophilus; with the split-up of that genus into several genera, it becomes problematical as to which of the present genera are involved.

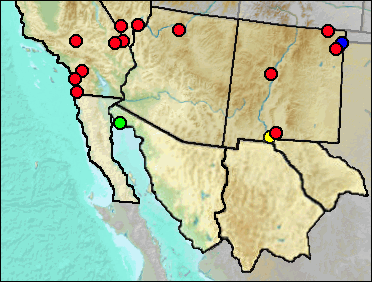

Sites.

Pleistocene: Perico Creek (Morgan and Lucas 2005).

Late Pleistocene: Wanis View (Jefferson 2014).

Latest Blancan: La Union (Morgan and Lucas 2003).

Irvingtonian: El Golfo (Croxen et al. 2007).

Rancholabrean: Tramperos Creek (Morgan and Lucas 2005).

Rancholabrean/?Early Holocene: Mitchell Caverns (Jefferson 1991b).

Wisconsin: CC:5:5 (Mead et al. 2003); Glen Abby, Bonita (Majors 1993).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Rampart Cave (Lindsay and Tessman 1974); Mid/Late Wisconsin: Diamond Valley (Springer et al. 2009).

Late Wisconsin: Antelope Cave [two species] (Jefferson 1991b); Folsom Site (Morgan and Lucas 2005); Potosi Mountain (Mead and Murray 1991.

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Conkling Cavern (Conkling 1932); Isleta Cave No. 2 (?) (UTEP); Newberry Cave (Jefferson 1991b); Schuiling Cave (Jefferson 1991b).

Literature. Conkling 1932; Croxen et al. 2007; 1991b; 2014; Lindsay and Tessman 1974; Mead and Murray 1991; Majors 1993; Mead et al. 2003; Morgan and Lucas 2003, 2005; Springer et al. 2009.

Synonyms. Citellus cochisei

There is insufficient information to allow placement within one of the currently recognized North American genera.

Fig. 1. Spermophilus cochisei: palatal view of holotype (1); dorsal and lateral views of paratype (2, 2a). After Gidley 1922 (images have been manipulated for clarity).

Gidley's (1922) description follows:

Type.—Portion of a right maxillary containing

all the cheek teeth (catalog No. 10490, U.S. Nat. Mus.).

Paratype.—Portion of a left lower jaw (catalog

No. 10491).

Locality.—Both are from the Curtis locality, in sec. 25, T. 18 S., R. 21 E., and were found in

exhuming a mastodon skeleton.

Description.—Length of upper cheek-tooth series 10.5 millimeters. Molars relatively wide,

m1 and m2 one-third wider than long; lophs and valleys simple and narrow; both posterior

transverse lophs of the molars completely united with protocone, forming a short, narrow

valley opening outward and extending inward not more than one-half the width of the tooth

crown, as in Cynomys. The anterior transverse lophs are more depressed and except in

m3 are much longer than the other lophs, extending inward and upward to disappear in the

anterior wall of the protocone. P4 differs from the anterior two molars only in being less

wide and in having the anterior loph relatively and actually more extended anteriorly.

In the greater width of tooth crowns, the less extent of their median external reentrant valleys,

and the relative shortness of the heel of the last molar, this species suggests Cynomys,

but it differs from species of that genus in the much more brachyodont tooth crowns, the

greater relative depth of the median external reentrant valleys, and the incipiency, amounting

to almost total absence, of the posterior reentrant valleys so prominent in species of

Cynomys. The first of these features might be considered as a character of degree only, indicating less advanced specialization, but the

other two I consider characters that denote relationship with the living species of Citellus

rather than with those of the genus Cynomys.

The lower jaw, as indicated by specimen No. 10491, which carries the incisor and the anterior

two cheek teeth, is relatively short and deep, the incisor narrow and pointed, and the

cheek teeth relatively wide to a degree corresponding with those of the upper series.

This species compares in size with C. evermani, but it differs from all the living forms in one or

more of the characters enumerated above.

Sites.

Late Blancan: Curtis Ranch (Lindsay 1984); Prospect (Johnson et al. 1975).

Literature. Gidley 1922; Lindsay 1984; Johnson et al. 1975.

Last Update: 28 May 2015