Class Reptilia

Order Squamata

Suborder Serpentes

Family Crotalidae

Crotalus sp.—Rattlesnakes //Crotalus atrox—Western Diamondback Rattlesnake // Crotalus lepidus—Rock Rattlesnake // Crotalus michellii/oreganus—Speckled or Western Rattlesnake // Crotalus michellii—Speckled Rattlesnake // Crotalus oreganus—Western Rattlesnake // Crotalus molossus—Black-tailed Rattlesnake // Crotalus scutulatus—Mohave Rattlesnake // Crotalus viridis—Prairie Rattlesnake

The pitvipers include

the rattlesnakes, Copperhead, and Cottonmouth. The name of the family refers to its

members having a pit (Fig. 1) on the side of the head that detects infrared radiation,

and thus is able to accurately locate the position of warm-blooded prey in the

dark.

The pitvipers include

the rattlesnakes, Copperhead, and Cottonmouth. The name of the family refers to its

members having a pit (Fig. 1) on the side of the head that detects infrared radiation,

and thus is able to accurately locate the position of warm-blooded prey in the

dark.

The Copperhead and Cottonmouth occur only east of our region. However, the region hosts a large number of species of rattlesnake, all of which are placed in the genus Crotalus except for the Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus). Although crotalid vertebrae are distinctive from those of other snakes of our region, few if any species are identifiable with certainty on the basis of vertebrae. Although there are differences in adult size among the species, this seldom is conclusive in identification.

Fig. 1. Black-tailed Rattlesnake showing the position of the pit (within the white rectangle). The nostril is separate and located just above the rectangle toward the right. Photograph by A. H. Harris.

All members of the family are venomous with a sophisticated injection system. The fangs, located at the front of the mouth, normally are folded back, but become erect when the mouth opens for a strike. The fangs are hollow, with the cavity being connected with the poison glands; an opening toward the distal, anterior portion of a fang allows injection of the venom. The venom is primarily for the acquisition of prey, but of course also is utilized as a defensive weapon.

Rattlesnakes can be found in the Southwest in virtually every habitat from low desert into high-mountain forested areas. Their remains are frequent in cave deposits, presumably from a combination of often seeking protection from hot weather and hibernating in crevices and caves and in hunting small mammals such as woodrats that often inhabit caves. During excavations at U-Bar Cave, living rattlesnakes were present on a number of occasions.

Although identification to genus is reasonably secure, there appears to be no published characters reliably separating the species on the basis of vertebral characters, other than some species reaching a larger maximum size. The Howell's Ridge Cave specimens include a medium-sized and a small-sized species (Van Devender and Worthington 1977). They mention five species as possibilities, including C. lepidus and C. viridis; the specimens identified by them (UTEP collection) include two tentative species identifications: C. lepidus and C. viridis (see account, below); it's unclear whether these identifications represent further study after the publication was submitted or just represent identifications the authors were unwilling to submit to print.

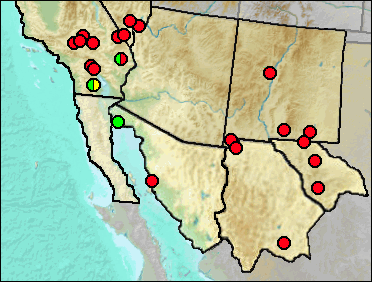

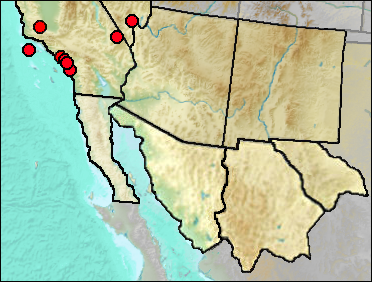

Sites.

Late Blancan/Irvingtonian: Vallecito Creek, Anza-Borrego Desert (Cassiliano 1999).

Irvingtonian: El Golfo (Croxen et al. 2007).

Irvingtonian/Rancholabrean: Cadiz (Jefferson 2014).

Rancholabrean: Bitter Springs Playa (Jefferson 2014); Devil Peak (Reynolds, Reynolds, and Bell 1991); Hoffman Road (Jefferson 2024); Lake View Hot Springs (Jefferson 2014); Marlett Locality (White et al. 2010); Piute Ponds (Jefferson 2014).

Early/Early-Mid Wisconsin: Lost Valley (UTEP); Rm Vanishing Floor (Harris 1993c).

Mid Wisconsin: Devil Peak (Jefferson et al. 2015); Pendejo Cave (Harris 2003); U-Bar Cave (Harris 1987).

Mid/Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Jimenez Cave (Messing 1986); Sierra Diablo Cave (UTEP).

Late Wisconsin: Algerita Blossom Cave (Harris 1993c); Animal Fair 18-20 ka (Harris 1989); Antelope Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991); Balcony Room (UTEP); Beyond Bison Chamber (Harris 1993c); Camel Room (Harris 1993c); Charlies Parlor (Harris 1989); Dust Cave (this work); Harris' Pocket (Harris 1989); Mountain View Country Club (Jefferson 2014); Pendejo Cave (Harris 2003); Shafter Midden (UTEP); TT II (Harris 1993c); U-Bar Cave 13-14 ka (Harris 1989); U-Bar Cave 14-15 ka (Harris 1989); U-Bar Cave 15-18 ka (Harris 1989); U-Bar Cave 18-20 ka (Harris 1989); Upper Sloth Cave (Logan and Black 1979); Vulture Cave (Van Devender et al. 1977a).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Beyond Bison Chamber (Harris 1993c); Fowlkes Cave (Parmley 1990); Howell's Ridge Cave (Van Devender and Worthington 1977); Isleta Cave No. 2 (UTEP); Kokoweef Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991 [two species]); Newberry Cave (Jefferson 1991a); Pendejo Cave (Harris 2003).

Literature. Cassiliano 1999; Croxen et al. 2007; Harris 1987, 1989, 1993c, 2003; Jefferson 1991a, 2014; Logan and Black 1979; Messing 1986; Parmley 1990; Reynolds, Reynolds, and Bell 1991; Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991; Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991; Van Devender and Worthington 1977; Van Devender et al. 1977a.

Holman's (1970) identification of this species from

the Dry Cave sites of Bison Chamber and Balcony Room is based on two skull parts, a maxilla and a

right angular. Brattstrom (1964) noted over 3,000 diamondback vertebrae in just one box of elements

from Shelter Cave; other specimens were present from all sections. He also had available various

cranial elements.

Holman's (1970) identification of this species from

the Dry Cave sites of Bison Chamber and Balcony Room is based on two skull parts, a maxilla and a

right angular. Brattstrom (1964) noted over 3,000 diamondback vertebrae in just one box of elements

from Shelter Cave; other specimens were present from all sections. He also had available various

cranial elements.

Fig. 1. Western Diamondback Rattlesnake. Photograph courtesy of Carl S. Lieb.

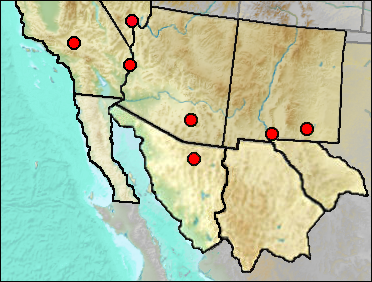

Sites.

Sangamon: La Brisca (Van Devender et al. 1985).

Mid Wisconsin-Holocene: Shelter Cave (Brattstrom 1964).

Late Wisconsin: Bison Chamber (Holman 1970); Gypsum Cave (Brattstrom 1954); Tunnel Ridge Midden (Jefferson 1991a).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Balcony Room (Holman 1970); Conkling Cavern (Brattstrom 1964); Deadman Cave (Mead et al. 1984); Fosberg Cave (Brattstrom 1964); Schuiling Cave (Jefferson 1991a).

Literature. Brattstrom 1954, 1964; Holman 1970; Jefferson 1991a; Mead et al. 1984; Van Devender et al. 1985.

Sites.

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Diamond Valley (Springer et al. 2009: cf.).

Literature. Springer et al. 2009.

Sites.

Currently this small snake occupies southeastern Arizona east across southern New Mexico to southwestern Texas and south into Mexico.

Late Blancan: Curtis Ranch (Brattstrom 1955: cf.)

Literature. Brattstrom 1955.

These are relatively small rattlesnakes. Crotalus oreganus was included in Crotalus viridis until recently (see Crotalus viridis account).

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Desert Almond (Van Devender et al. 1977a); Vulture Cave (Mead and Phillips 1981)

Literature. Mead and Phillips 1981; Van Devender et al. 1977a.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Gypsum Cave (Brattstrom 1954)

Literature. Brattstrom 1954.

Northern populations of Black-tailed Rattlesnakes recently have been recognized as actually consisting of two species, Crotalus molossus and C. ornatus (Anderson and Greenbaum 2012). Populations west of southwestern New Mexico are recognized as C. molossus, but relatively little change in the boundary would put C. ornatus into the California Wash area.

Sites.

Late Blancan: California Wash (Lindsay 1984: cf.).

Literature. Anderson and Greenbaum 2012; Lindsay 1984.

Synonyms. Crotalus viridis.

Sites.

?Late Irvingtonian/Rancholabrean: Emery Borrow Pit (Jefferson 1991a).

Rancholabrean: Mescal Cave (Jefferson 1991a).

Sangamon: Newport Bay Mesa (Jefferson 1991a); San Pedro Lumber Co. (Jefferson 1991a).

Wisconsin: Costeau Pit (Jefferson 1991a).

Mid Wisconsin: McKittrick (Jefferson 1991a); Rancho La Brea (LaDuke 1991).

Late Wisconsin: Gypsum Cave (Brattstrom 1954)

Mid/late Wisconsin: San Miguel Island (Guthrie 1993).

Literature. Brattstrom 1954; Guthrie 1993; Jefferson 1991a; LaDuke 1991.

"The Mohave rattlesnake is a common desert-grassland and desertscrub snake in southern Arizona and near Deadman Cave today" (Mead et al. 1984:260).

Sites.

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Deadman Cave (Mead et al. 1984).

Literature. Mead et al. 1984.

Until early in this century, populations assigned to

C. viridis occurred across the western U.S. DNA evidence that two major phylogenetic groups

were included under that name resulted in splitting the species into a western species (C.

oreganus) and an eastern species that retains the name C. viridis. Most of New Mexico

falls into the modern geographic range of C. viridis; C. oreganus occurs throughout

Arizona and extends eastward into the highlands of west-central New Mexico. Specimens tentatively

identified by Van Devender (UTEP collection) from Howell's Ridge Cave as C. viridis are

from an area that might have been inhabited by C. oreganus. These specimens were listed only

to genus in Van Devender and Worthington (1977).

Until early in this century, populations assigned to

C. viridis occurred across the western U.S. DNA evidence that two major phylogenetic groups

were included under that name resulted in splitting the species into a western species (C.

oreganus) and an eastern species that retains the name C. viridis. Most of New Mexico

falls into the modern geographic range of C. viridis; C. oreganus occurs throughout

Arizona and extends eastward into the highlands of west-central New Mexico. Specimens tentatively

identified by Van Devender (UTEP collection) from Howell's Ridge Cave as C. viridis are

from an area that might have been inhabited by C. oreganus. These specimens were listed only

to genus in Van Devender and Worthington (1977).

Fig. 1. Prairie Rattlesnake. Photograph by Carl S. Lieb.

The Prairie Rattlesnake reaches higher elevations than other species in the region, and this may be partly the basis for the identification from the high-elevation SAM Cave.

Sites.

Medial Irvingtonian: SAM Cave (Rogers et al. 2000).

Literature. Rogers et al. 2000; Van Devender and Worthington 1977

Last Update: 25 May 2015