Class Aves

Order Accipitriformes

Family Cathartidae

Fig. 1. Gymnogyps californianus. Photograph by Noel Synder, courtesy

of the US Fish & Wildlife Service.

Fig. 1. Gymnogyps californianus. Photograph by Noel Synder, courtesy

of the US Fish & Wildlife Service.

The living California Condor and the Pleistocene condors, especially the condor represented in the Rancho La Brea deposits, have either been considered as separate species (G. californianus and G. amplus) or the Pleistocene form has been considered a temporal subspecies of G. californianus. The primary difference used to separate the two taxa was size, the Pleistocene form being larger. Howard (1962:241) did note "the presence of a pair of markedly swelled ridges, one on either side and extending along the median line of the ventral surface of the nasal process of the premaxilla" in one specimen from Howell's Ridge Cave and the probable occurrence on a second specimen. This was in contrast to specimens from Rancho La Brea and Rocky Arroyo Cave (= Burnet Cave).

In the original account here, G. amplus was considered a synonym of G. californianus, though it was noted that in a 2007 presentation, Syverson and Prothero presented results of an extensive comparison of the Rancho La Brea and modern condor specimens and concluded that they represent separate species. They since (2010) have published their evidence. Their conclusion is accepted here, but the specific status of most specimens in the interior of North America is now unclear. Part of the problem is that Syverson and Prothero (2010) give only means and variances and for only a few elements (skull, humerus, and femur); equally important, most published records for the Southwest do not include measurements. With largely fragmentary material, few elements available from the New Mexico/Trans-Pecos region provide measurements comparable to those of Syverson and Prothero. The few available (Dark Canyon Cave) are generally relatively large, suggesting that G. amplus is the species represented in that cave.

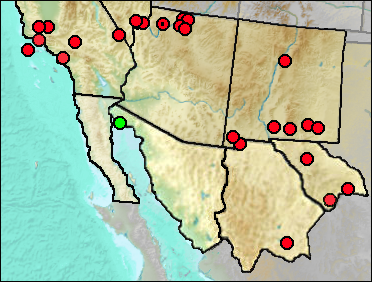

Although the

distribution of modern condors is limited to California and introductions into Arizona

and Nevada, past distribution of condors apparently was far greater, with the birds

withstanding Pleistocene climatic conditions as far east and north as the state of New

York (Steadman and Miller 1987).

Although the

distribution of modern condors is limited to California and introductions into Arizona

and Nevada, past distribution of condors apparently was far greater, with the birds

withstanding Pleistocene climatic conditions as far east and north as the state of New

York (Steadman and Miller 1987).

Fig. 2. Left to right: left coracoid, proximal left tarsometatarsus, distal right ulna of condors from Howell's Ridge Cave. UTEP specimens. Scale in mm.

Emslie (1987) recorded dates for a number of fossil condors from caves in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Dates ranged from 22,180 ± 400 to 9580 ± 160 BP. Mead et al. (2003) indicated that condors inhabited the Grand Canyon from at least 42 ka (apparently based on dating of a condor feather from site CC:5:2) to about 10 ka. Material from the New Mexico/Texas region included dates from Howell's Ridge Cave (13,460 ± 220), U-Bar Cave (13,030 ± 180), Dark Canyon Cave (9585 ± 310), Rocky Arroyo Cave (12,180 ± 130), Mules Ear Peak Cave (12,580 ± 135), and Maravillas Canyon (10,215 ± 320). Thus, as Emslie hypothesized, inland populations apparently were gone by around 10,000 radiocarbon years BP.

Howard and Miller (1933) recorded California Condor from Shelter Cave. However, Howard (1971) later compared the elements with those of Breagyps clarki and assigned the Shelter Cave material to that species.

Sites.

Irvingtonian: El Golfo (Croxen et al. 2007).

Late Rancholabrean: Luka Cave (DeSaussure 1956); Tooth Cave (DeSaussure 1956).

Wisconsin: Carpinteria (Guthrie 2009); McKittrick (Jefferson 1991a).

Mid Wisconsin. CC:5:2 (Mead et al. 2003).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Dark Canyon Cave (Howard 1971); Rampart Cave (Wilson 1942); Rancho La Brea (Stock and Harris 1992); Sandblast Cave (Emslie 1988); San Miguel Island (Guthrie 1998).

Mid/Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Jimenez Cave (Messing 1986); Sierra Diablo Cave (UTEP).

Late Wisconsin: Antelope Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991: cf.); Bridge Cave (Emslie 1987); Ceremonial Cave (Cosgrove 1947); Gypsum Cave (Jefferson et al. 2015); Howell's Ridge Cave (Howard 1962); Maravillas Canyon (Emslie 1987); Maricopa (Jefferson 1991a); Marmot Cave (Brasso and Emslie 2006); Midden Cave (Mead et al. 2005); Mule Ears Peak (Wetmore 1933); Sandia Cave (Brasso and Emslie 2006); Skull Cave (Emslie 1988); Skylight Cave (Emslie 1988); Stanton's Cave (Rea and Hargrave (1984); Stevens Cave (Emslie 1988); U-Bar Cave 13-14 ka; Vulture Cave (Mead and Phillips 1981).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Burnet Cave (Wetmore 1931; Emslie 1987); Conkling Cavern (Howard and Miller 1933); Kokoweef Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991); Newberry Cave (Jefferson 1991a); Schuiling Cave (Jefferson 1991a).

Literature. Brasso and Emslie 2006; Cosgrove 1947; Croxen et al. 2007; DeSaussure 1956; Emslie 1987, 1988; Guthrie 1998, 2009; Howard 1962, 1971; Howard and Miller 1933; Jefferson 1991a; Jefferson et al. 2015; Mead and Phillips 1981; Mead et al. 2003; Mead et al. 2005; Messing 1986; Rea and Hargrave 1984; Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991; Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991; Steadman and Miller 1987; Stock and Harris 1992; Syverson and Prothero 2010; Wetmore 1931, 1933; Wilson 1942.

Last Update: 6 Apr 2015