Class Mammalia

Order Artiodactyla

Suborder Ruminantia

Family Cervidae

Sites.

Irvingtonian: El Golfo (Croxen et al. 2007: cf.).

Late Wisconsin: Antelope Cave ((Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991: ? gen.); Sandia Cave (Thompson and Morgan 2001:

?)

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Howell's Ridge Cave (Harris 1993c: ?).

Literature.

Croxen et al. 2007; Harris 1993c; 1991b; Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991; Thompson and Morgan 2001.

Synonyms. Rangifer fricki Schultz and Howard 1935; Sangamona Hay 1920.

Schultz and Howard (1935) identified several cervid elements from Burnet Cave as Sangamona? sp., remarking that the size was intermediate between Odocoileus and Cervus. They also named a new species of cervid, Rangifer? fricki. Kurtén (1975) erected a new genus, Navahoceros, with Rangifer? fricki as the type species. His diagnosis reads (p. 507): "Medium to large sized cervids with very thick-set limb bones and short metapodials; males with simple forked antlers; females antlerless."

Kurtén included material that Schultz and Howard had tentatively assigned to Sangamona, an antler base that is the type of Cervus lascrucensis, and the Mexican fossil species, Odocoileus halli.

Kurtén and Anderson (1980) considered N. lascrucensis a synonym of N. fricki, an approach earlier adopted here for convenience. However, Morgan and Lucas (2003) list it as N. lascrucensis, and Morgan et al. (2011) tentatively regarded N. lascrucensis as a late Blancan and early Irvingtonian species. This judgement is accepted here.

Hay (1927) described Cervus? lucasi on the basis of a first phalanx and an astragalus. Morejohn and Dailey (2004) assigned cervid specimens from Honey Lake, Lassen County, California, to this species, but transferred Hay's taxon to Odocoileus on the basis of characters assignable to that genus; apparently the similar geological ages of the type material and the Californian specimens played a part in the assignment since no data were given to otherwise indicate conspecificity. In their "Discussion and Conclusions" section, they noted that numerous remains of specimens identified as Navahoceros were examined during their research and determined by them to be Odocoileus. They concluded that Navahoceros fricki is a nomen nudum. They ventured no opinion on the specific status of the Navahoceros material, though their assignment of O. lucasi to a geologic age of "Plio-Pleistocene (2.5 mya-700,000 ya)" (p. 6) would seem to rule out their considering the Navahoceros material as conspecific with O. lucasi.

The primary focus of Morejohn and Dailey (2004) was in establishing morphological criteria to distinguish Old World emigrants from New World taxa. The North American taxa studied were the Old World emigrants Cervus elaphus (Elk) and Alces alces (Moose) versus Odocoileus hemionus (Mule Deer), Odocoileus viriginianus (White-tailed Deer), and Rangifer tarandus (Reindeer). Odocoileus was determined to be separate from the Old World taxa and Rangifer, but not from Navahoceros on the basis of their criteria. In essence, by ruling out all genera except Odocoileus on postcranial, morphological grounds, Navahoceros was left as being a member of Odocoileus. This, however, assumes that all taxa having the characters by which they separated Odocoileus from the other genera are assignable to Odocoileus.

Webb (1992) concluded on the basis of cranial criteria that Navahoceros is the sister taxon of Rangifer, a judgment unlike that of Morejohn and Dailey. Regardless of whether Navahoceros is more closely related to Rangifer or to Odocoileus, it appears to me that the cranial and postcranial differences makes assignment to a separate genus, Navahoceros, defensible; thus Navahoceros as a distinct genus is accepted here.

Vanderhill (1986) referred two regional items from the Frick Collection (American Museum of Natural History) to Navahoceros. One is the holotype of Cervus lascrucensis. The other is a metatarsal differing in dimensions from all known Plio-Pleistocene North American cervids except N. fricki. According to Vanderhill, Navahoceros fossils at the American Museum of Natural History were collected from the stretch of basin-fill from near Chamberino, New Mexico, south to opposite Canutillo, Texas, by Joseph Rak in 1929. Although the type of Cervus lascrucensis is listed by Kurtén as Cueva Las Cruces, Vanderhill found no mention of a cave in the American Museum records and preservation is similar to other specimens collected from the basin-fill sediments.

Fig. 1. Anterior and posterior views of the anterior cannonbone (UTEP 5689-103-1) of Navahoceros fricki from U-Bar Cave. Scale is metric.

Fig. 2. Anterior cannon bones of (left to right) Cervus elaphus, Navahoceros fricki, and Odocoileus hemionus to illustrate size and proportion differences.

Sites.

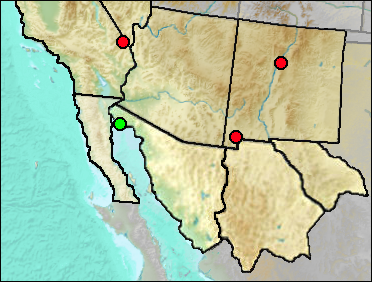

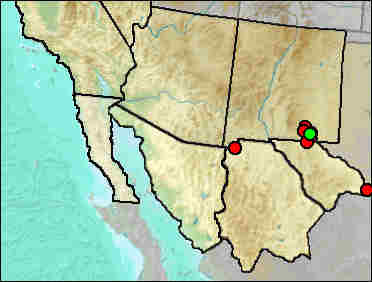

Medial Irvingtonian: Slaughter Canyon Cave (Kurtén 1975).

Wisconsin: Big Manhole Cave (Harris 1993c: cf.).

Mid Wisconsin: U-Bar Cave (Harris 1993c).

Late Wisconsin: Burnet Cave (Schultz and Howard 1935); Cueva Quebrada (Lundelius 1984); Hermit's Cave (Schultz et al. 1970); Mystery Light Cave (this volume: cf. gen.); U-Bar Cave (UTEP).

Literature.

Harris 1993c; Hay 1927; Kurtén 1975; Kurtén and Anderson 1980; Lundelius 1984; Morejohn and Dailey 2004; Morgan and Lucas 2003; Morgan et al. 2011; Schultz and Howard 1935; Schultz et al. 1970; Thompson and Morgan 2001; Vanderhill 1986; Webb 1992.

With tentative acceptance of N. lascrucensis as a valid species, the type is transferred from consideration as N. fricki to this account. Morgan et al. (2011) were unable to pinpoint the stratigraphic level of the type (an antler base), but were able to narrow the age to either late Blancan or early Irvingtonian. The Caballo specimen is a partial antler and described in some detail by Morgan et al. (2011).

Sites.

Late Blancan: Caballo (Morgan et al. 2011: cf.).

Late Blancan/Early Irvingtonian: La Union or Adobe Ranch (Morgan et al. 2011).

Literature.

Last Update: 4 Feb 2016