Class Mammalia

Order Eulipotypla

Family Soricidae

Sorex sp.—Long-tailed Shrew // Sorex arizonae—Arizona Shrew // Sorex cinereus—Masked Shrew // Sorex leahyi—Leahy's Shrew // Sorex merriami—Merriam's Shrew // Sorex monticola—Montane Shrew // Sorex nanus—Dwarf Shrew // Sorex navigator—Western Cordilleran Water Shrew // Sorex neomexicanus—New Mexican Shrew // Sorex ornatus—Ornate Shrew // Sorex preblei—Preble's Shrew // Sorex tenellus—Inyo Shrew // Sorex trowbridgii—Trowbridge's Shrew

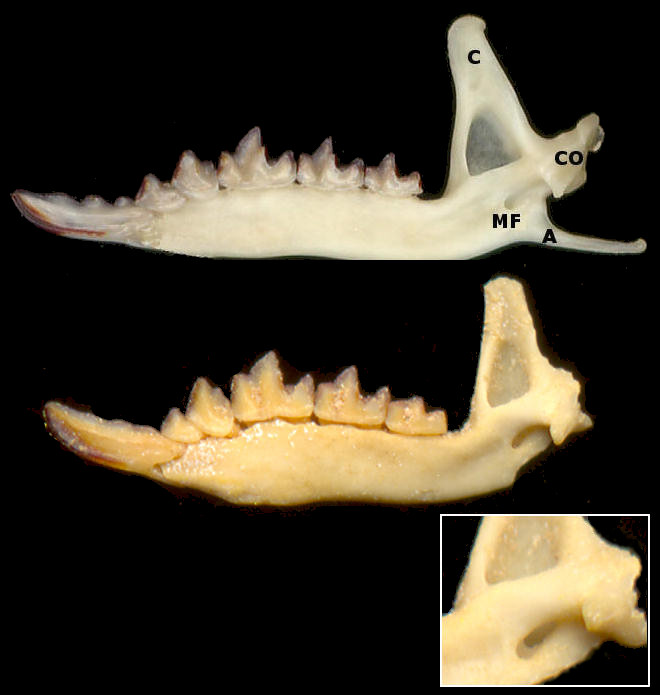

Most of the North American shrews belong to the genus Sorex. These are characterized by (among other characters) the possession of five upper unicuspids. Differences in absolute and relative sizes of these teeth will discriminate among many of the species. Another frequently preserved character that divides long-tailed shrews into two groups is the presence or absence of a post-mandibular foramen (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Ventral view of the skull of Sorex monticolus. The inset labels the teeth, with parts of some teeth outlined to make clear the overall shape.

North American shrews have portions of their teeth pigmented, though quite lightly so in the genus Notiosorex. The dark reddish pigment is apparent in Fig. 1. The first four of the unicuspids in the figure have a pigmented ridge or cusplet medially. Sorex monticolus has the fourth unicuspid larger than the third; the fifth unicuspid is very small; this can be seen in the image, although it shows up better in lateral view. Other characters of the family Soricidae also can be seen in Fig. 1, including the lack of zygomatic arches and auditory bullae. The paired whitish ovals within the spaces under the cranium hold the eardrums in life; the projection into each space enclosed by an oval is a middle ear ossicle, the malleus.

Fig. 2 Medial views of right dentaries of a modern specimen of Montane Shrew (Sorex monticolus, top) and a fossil specimen of Merriam's Shrew (Sorex merriami). Illustrations are only approximately to scale. The angular process and part of the condyloid process are missing in the Merriam's Shrew. The inset shows a larger view of the posterior portion of the dentary of S. merriami, showing the presence of both mandibular foramen and post-mandibular foramen. Abbreviations: C, coronoid process; CO, condyloid (articular) process; MF, mandibular foramen; A, angular process.

The genus Sorex is primarily northern in distribution. In the western United States, it extends southward along the major mountain chains and occurs at high elevations in many isolated highlands. Highlands in the Southwest were connected by shrew habitat allowed by lowered summer temperatures and increased effective moisture during glacial ages; as the last glacial age came to an end, populations found themselves marooned in the uplands by unsuitable surrounding habitat. The distribution of fossil Sorex documents these changes.

Fragmentary material lacking specific diagnostic features often can be identified to genus. This is the case with the records reported here as "Sorex sp."

Sites.

Late Blancan: Tecopa Lake Beds (Whistler and Webb 2005).

Irvingtonian: El Golfo (Croxen et al. 2007); Shutt Ranch, San Timoteo Badlands (Albright 2000).

Medial Irvingtonian: SAM Cave (Rogers et al. 2000).

Late Irvingtonian: Elsinore: Pauba Formation (Pajak et al. 1996).

Rancholabrean: National City West (Jefferson 2014).

Rancholabrean/Early Holocene: Metro Rail Universal City Station (Jefferson 2014); (Jefferson 2014).

Mid Wisconsin: McKittrick (Jefferson 1991b: as Microsorex sp.).

Late/Mid Wisconsin: Screaming Neotoma Cave (Glennon 1994).

Late Wisconsin: Algerita Blossom Cave (Harris 1993c); Antelope Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991); Burnet Cave (Harris 1993c).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Burnet Cave (Harris 1993c); SAM Cave (Rogers et al. 2000).

Literature. Albright 2000; Croxen et al. 2007; Glennon 1994; Harris 1993c; Jefferson 1991b, 2014; Pajak et al. 1996; Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991; Rogers et al. 2000; Whistler and Webb 2005.

Sorex arizonae occurs now in mountains of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, thence south into the Sierra Madre of Mexico.

Sites.

Mid Wisconsin: Papago Springs Cave (Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999).

Literature: Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999; Diersing and Hoffmeister 1977.

The Masked Shrew's current range comes south to northern New Mexico; it is not known south of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. As with many shrews, mesic habitat is required. The likely occurrence of marshy areas along Blackwater Draw could well have supplied suitable habitat. The other records are from the main mountain mass of the Guadalupe Mountains; it has not been recognized from the large mammalian faunas that lie to the east of the Guadalupes.

Sorex cinereus is a very small shrew. It shares with S. merriami and S. arizonae the characteristic of third and fourth upper unicuspids being approximately the same size (Fig. 1), but differs from them, among other things, in that there is a pigmented ridge running from apex of tooth lingually to the medial cingulum of tooth where it ends in a small pigmented cusplet. In other species found in the region, the third upper unicuspid is smaller than the fourth.

Fig. 1. Sorex cinereus. Ventral view of skull, rostral area, and lingual and labial views of dentary. Note that there is a fifth upper unicuspid, but is so small as to easily be missed. The atlas is still attached to the posterior skull, concealing the foramen magnum.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Blackwater Draw (Slaughter 1975); Muskox Cave (Logan 1981); Lower Sloth Cave (Logan 1983); Upper Sloth Cave (Logan and Black 1979).

Literature. Logan 1981, 1983; Logan and Black 1979; Slaughter 1975.

Sites.

Late Blancan: Jack Rabbit Trail, San Timoteo Badlands (Albright 2000).

Literature. Albright 2000.

Merriam's Shrew is adapted to somewhat less mesic conditions than other members of the genus. Hafner and Stahlecker (2002) summarized the current distribution of S. merriami in New Mexico and commented on the ecology. They pointed out that about half of the New Mexican records of the species "correspond with relictual stands of Great Basin sagebrush steppe" (p. 136), and that the southern limits of the shrew and of Big Sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) nearly coincide. Where it has not been taken in sagebrush steppe habitats, vegetation includes dry areas in coniferous forest and open grassland.

Sites.

Wisconsin: Big Manhole Cave (Harris 1993c).

Early/Early-Mid Wisconsin: Lost Valley (Harris 1993c).

Mid Wisconsin: Pendejo Cave (Harris 2003); U-Bar Cave (Harris 1987).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Dark Canyon Cave (Harris 1993c).

Late Wisconsin: Animal Fair 18-20 ka (Harris 1989); Bison Chamber (Harris 1970a); Charlies Parlor (Harris 1989); Dust Cave (Harris and Hearst 2012); Harris' Pocket (Harris 1970a); Lower Sloth Cave (Harris, this work); Muskox Cave (Logan 1981); Sheep Camp Shelter (Gillespie 1985); Stalag 17 (Harris 1993c); TT II (Harris 1993c); U-Bar Cave 14-15 ka (Harris 1989: cf.).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Balcony Room (Harris 1993c); Pendejo Cave (UTEP)..

Literature. Gillespie 1985; Hafner and Stahlecker 2002; Harris 1970a, 1987, 1989, 1993c, 2003; Harris and Hearst 2012; Gillespie 1985; Logan 1981.

Synonyms. Sorex vagrans.

In its modern ecology, the Montane Shrew lives up to its name in Arizona and New Mexico (it's unknown from Trans-Pecos Texas), being limited to higher elevations; this is especially the case in the southern parts of the states. This normally means coniferous forest habitats, from mesic areas near water in Ponderosa Pine forest to spruce-fir forest. Findley et al. (1975) estimated a current lower elevational limit of perhaps 7400 ft in New Mexico.

Tebedge (1988) recorded Sorex vagrans on plentiful material from Dark Canyon Cave. There are two problems. One is nomenclatural: Since 1988, the name S. vagrans has been restricted to populations outside of our region, with the New Mexican populations earlier recognized as S. vagrans becoming known as Sorex monticola; the southeastern populations later were separated from S. monticola as S. neomexicanus. The other potential problem is involved in identification. It appears that Tebedge was primarily concerned with separating S. vagrans from Sorex cinereus, but failed to consider the possibility of Sorex merriami. Sorex merriami shares some upper unicuspid characters with S. cinereus and his specimens with upper unicuspids present fit the pattern of S. neomexicanus, but not S. merriami or S. cinereus. Thus S. neomexicanus is recognized as being present in the Dark Canyon Cave fauna in the S. neomexicanus account. His comparison of lower mandibles, however, appears to be strictly between S. neomexicanus and S. cinereus. It thus is not unlikely that S. merriami may have been present in his material. Differentiation of the two species is largely dependent on the presence or absence of the post-mandibular foramen, absent in S. neomexicanus and present in S. merriami (see Fig. 1 under Sorex sp.). The only two shrew dentaries from Dark Canyon Cave in the UTEP collection represent S. merriami.

Findley (1965) described S. vagrans from Hermit Cave in the Guadalupe Mountains. He noted that the fossil specimens did not resemble the nearest modern populations in size, being smaller. Populations nearer in size to the fossils occur now in western New Mexico and in northern New Mexico. The Hermit Cave specimens have arbitrarily been placed in S. neomexicanus, but may actually represent S. monticola.

Sites.

Mid Wisconsin: U-Bar Cave (Harris 1993c: cf.).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Baldy Peak Cave (Harris 1993c); Bat Cave (Scarbrough 1986).

Literature. Findley 1965; Findley et al. 1975; Harris 1993c; Scarbrough 1986; Tebedge 1988.

Findley (1965) originally identified Sorex nanus from Hermit's Cave. With the discovery of Sorex preblei as fossils in the region, the specimens were rechecked (Harris and Carraway 1993) since the two taxa are of similar size, possibly resulting in misidentifications. However, Findley's identifications were confirmed.

Sites.

Wisconsin: Big Manhole Cave (UTEP).

Late Wisconsin: Dust Cave (Harris and Hearst 2012); Hermit's Cave (Findley 1965).

Literature. Findley 1965; Harris and Carraway 1993; Harris and Hearst 2012.

Until recently, Sorex palustris was considered to be present in our region, both today and in the Pleistocene; now, however, the species has been shown to consist of three species, with the earlier species name given to the taxon of our region being Sorex navigator (Woodman 2018). Sorex navigator tends to occur only where there is permanent water and water-associated vegetation. Its current range in our region is limited to the White Mountains of Arizona, the high mountains of northern New Mexico, and central California. Since the river valleys outside of that area are not occupied, it seems likely that hot summer temperatures may prevent occupation of such areas. This makes the occurrence at Fowlkes Cave, with many taxa currently limited to lowland semiarid habitats characterized by hot summers, puzzling unless, as suggested in the Fowlkes Cave site report, the fauna is mixed chronologically. The assignment to site age below reflects this suggestion.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Muskox Cave (Logan 1981).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Fowlkes Cave (Dalquest and Stangl 1984).

Literature. Dalquest and Stangl 1984; Logan 1981, Woodman 2018.

Synonyms. Sorex monticola, Sorex vagrans.

Early in North American mammalogy, numerous populations were named as species only to later be lumped with other populations into more inclusive species. This largely was upon acquisition of more material, especially from intermediate geographic localities. More recent trends, often based on DNA information or studies that could utilize larger samples, have been to recognize that many nominal species actually do consist of two or more species. Faced with the lack of diagnostic material and often the ability to reexamine material, paleontologists may have to resort to playing the geographic odds, assigning the new name to populations currently residing in or near the region.

Modern populations of one species of shrew from the Capitan and Sacramento mountains have in the not so distant past been considered as members of S. vagrans and, as S. vagrans was subdivided, as members of S. monticola. These populations have yet more recently been recognized as a different species than New Mexico populations recognized as S. monticola (Alexander 1996), with the next available name for these populations being Bailey's S. neomexicanus.

In this case, the problem is compounded by the recognition by Findley (1965) that shrews assignable to what at the time were assigned to S. vagrans were not of the large sized subspecies S. v. neomexicanus (= S. neomexicanus of current nomenclature). Rather, they were smaller and could reasonably be assigned to either S. v. monticola to the west or S. v. obscurus to the north. The question arises (as it does also with Microtus ochrogaster) as to whether we are seeing shifting of populations or responses by a population in situ to shifts in climate. In the former case, as suggested as a possibility by Findley, S. neomexicanus retained its current position at higher elevations while S. monticola was present in the lower elevations, including Hermit's Cave, becoming extirpated with warming and drying. In the latter case, the populations responded to end-Pleistocene warming and drying by moving up slope and individuals becoming larger.

Specimens from the present distribution of S. neomexicanus in southeastern New Mexico and Trans-Pecos Texas have arbitrarily been assigned to S. neomexicanus until someone can study additional specimens from the region. Some researchers recognize this taxon only as a subspecies of S. monticola (Woodman 2018).

Sites.

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Big Manhole Cave (Harris, this work); Dark Canyon Cave (Tebedge 1988).

Late Wisconsin: Animal Fair 18-20 ka (Harris 1989); Dust Cave (Harris and Hearst 2012); Harris' Pocket (Harris 1970a); Hermit's Cave (Findley 1965); Lower Sloth Cave (Logan 1983; only identifiable to S. merriami/neomexicanus [Harris, this work]); Muskox Cave (Logan 1981); TT II (Harris 1993c).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Balcony Room (Harris 1993c); Fowlkes Cave (Dalquest and Stangl 1984)

Literature. Alexander 1996; Dalquest and Stangl 1984; Findley 1965; Harris 1970a, 1989, 1993c; Harris and Hearst 2012; Logan 1981, 1983; Tebedge 1988, Woodman 2018.

The current distribution of this shrew is from northern California to the northern Baja California peninsula.

Sites.

Rancholabrean: Cool Water Coal Gasification Solid Waste Site (Jefferson 1991b).

Sangamon: Newport Bay Mesa (Jefferson 1991b).

Wisconsin: Carpinteria (Wilson 1933: cf.); Glen Abbey (Majors 1993: cf.).

Mid Wisconsin: McKittrick (Schultz 1937: cf.); Pacific City (Wake and Roeder 2009: cf.).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Diamond Valley (Springer et al. 2009); Rancho La Brea (Stock and Harris 1992); Tsuma Properties, San Clemente (Jefferson 2014).

Literature. Jefferson 1991b, 2014; Majors 1993; Schultz 1937; Springer et al. 2009; Stock and Harris 1992; Wake and Roeder 2009; Stock and Harris 1992; Wilson 1933.

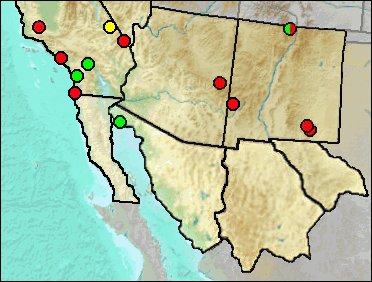

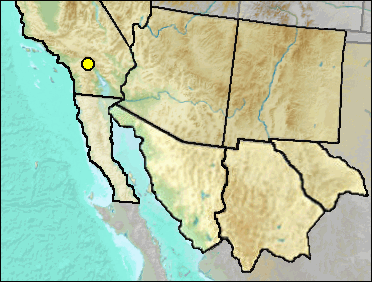

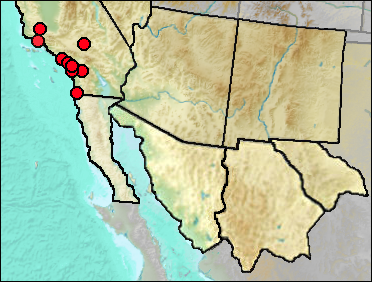

The geographic range of Sorex preblei is predominantly northwest and north of New Mexico (fig. 1), although Kirkland and Findley in 1996 reported it from the Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico. Since that publication, the shrew was reidentified as a relictual population of S. haydeni and then as an unnamed taxon allied with S. lyelli (Hope et al. 2012). Presence of this Jemez Mountains shrew in northern New Mexico leaves open the possibility that it is the taxon represented at Dry and U-Bar caves. UTEP specimen no. 22-1898 from the Animal Fair site within Dry Cave originally was identified as Sorex cf. nanus and MNM (now UTEP) 5689-140-16 from U-Bar Cave as Sorex sp. Both were re-identified in Harris and Carraway (1993) as Sorex preblei. Pending data allowing separation of the unnamed taxon from S. preblei, the records will be retained as published.

Fig. 1. Modern distribution of Sorex preblei. Adapted from Harris and Carraway (1993). The dot in northern New Mexico now refers to the unnamed taxon noted above, not S. preblei.

Sites.

Mid Wisconsin: U-Bar Cave (Harris and Carraway 1993).

Late Wisconsin: Animal Fair 18-20 ka (Harris and Carraway 1993).

Literature. Harris and Carraway 1993; Hope et al. 2012; Kirkland and Findley 1996; Tomasi and Hoffmann 1984.

Sorex taylori was named from the Blancan of Kansas.

Sites.

Late Blancan: California Wash (Morgan and White 2005).

Literature. Morgan and White 2005.

The Inyo Shrew currently occupies a restricted range in the mountains of western Nevada and eastern, central California.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Kokoweef Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991: ?)

Literature. Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991.

At present, Trowbridge's Shrew inhabits coniferous forests of the Coast Range, the Sierra Nevada, and the Cascades.

Sites.

Wisconsin: Carpinteria (Wilson 1933: cf.).

Mid Wisconsin: McKittrick (Jefferson 1991b: cf.).

Literature. Wilson 1933.

Last Update: 9 Apr 2019