UTEP Team Advances in Developing Vaccine for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

Last Updated on November 16, 2017 at 12:00 AM

Originally published November 16, 2017

By Lauren Macias-Cervantes

UTEP Communications

A research team at The University of Texas at El Paso is one step closer to developing an effective human vaccine for cutaneous leishmaniasis, a tropical disease found in Texas and Oklahoma, and affecting some U.S. troops stationed in Afghanistan and Iraq.

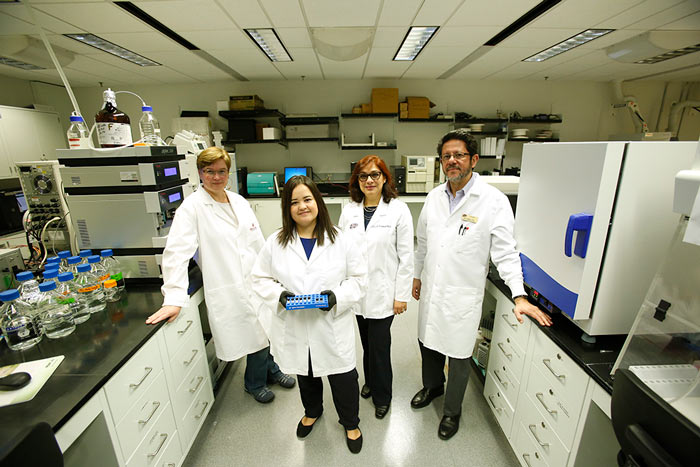

UTEP biological sciences doctoral student Eva Iniguez; her mentors Rosa Maldonado, Ph.D., and Igor Almeida, Ph.D.; and their teams and collaborators in Liverpool (Alvaro Acosta-Serrano, Ph.D.) and Saudi Arabia (Waleed Al-Salem, Ph.D.), recently published their research findings in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, the first journal solely devoted to the world’s most neglected tropical diseases.

Leishmaniasis is caused by the protozoan leishmania parasites, which are transmitted by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sandflies – flies that are three times smaller than a mosquito. According to the World Health Organization, there are an estimated 700,000 to 1 million new cases annually, and they cause 20,000-30,000 deaths each year. The disease affects some of the poorest people on Earth. Though it is found in more than 90 countries in the tropics, subtropics and southern Europe, naturally transmitted cases also have been found in the northeastern parts of Texas and in Oklahoma. The disease has impacted 2,000 U.S. troops stationed in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“I think we are in a very good position with this vaccine candidate,” Maldonado said. “I think it is very promising. If things go well, I think we will be able to introduce this vaccine for clinical use in the future.”

During the team’s more than four years of research at UTEP’s Border Biomedical Research Center, they discovered a vaccine formulation that resulted in a 96 percent decrease in the lesions caused by the illness and showed an 86 percent protection rate from the disease in mice. The team counted on the expertise of UTEP chemist Katja Michael, Ph.D., to synthesize molecules used in the study.

“It was really hard to get to this point,” Iniguez said. “There was a lot of standardization, but I am very happy. It is significant protection that we observed and we have all the immunology to understand how the vaccine is working in the system.”

Maldonado and Almeida have each studied Chagas disease for more than 25 years and recently received a patent for the first synthetic Chagas vaccine. That work helped them initiate this research with leishmaniasis, as molecules are different in the diseases but there are similar carbohydrates between the parasites.

The team has submitted a patent application for their cutaneous leishmaniasis vaccine. Currently, there is no vaccine for the disease in humans. Treatment used now is very toxic, painful and lengthy – requiring patients to be hospitalized for almost three weeks for intravenous treatment. A vaccine does exist to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis in canines. It is approved for use in the United Kingdom.

More on leishmaniasis:

There are three forms of the disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes the effects of each:

Skin:

The skin sores of cutaneous leishmaniasis usually heal on their own, even without treatment. But this can take months or even years, and the sores can leave scars.

Mucosa:

Another potential concern applies to some (not all) types of the parasite found in parts of Latin America: certain types might spread from the skin and cause sores in the mucous membranes of the nose (most common location), mouth or throat (mucosal leishmaniasis). Mucosal leishmaniasis might not be noticed until years after the original sores healed. The best way to prevent mucosal leishmaniasis is to ensure adequate treatment of the cutaneous infection.

If not treated, severe (advanced) cases of visceral leishmaniasis typically are fatal.

Source: CDC