Class Mammalia

Order Chiroptera

Family Vespertilionidae

Myotis sp.—Myotis Bats // Myotis sp. (small)—Small Myotis // Myotis californicus—California Myotis // Myotis ciliolabrum—Western Small-footed Myotis // Myotis evotis—Long-eared Myotis // Myotis lucifugus—Little Brown Bat // Myotis occultus—Arizona Myotis // Myotis rectidentis—Straight-toothed Myotis // Myotis thysanodes—Fringed Myotis // Myotis velifer—Cave Myotis // Parastrellus hesperus—Western Pipistrelle

Members of this genus make up the majority of bat species in our region. They generally are relatively small and some living forms are difficult to identify even in hand. The basic dental formula is 2/3 1/1 3/3 3/3 = 38. However, Myotis occultus has a large proportion of its members with only two rather than three upper premolars, with a small percentage of Myotis lucifugus also following this pattern (Findley and Jones 1967). Occasional absence of premolars in members of other species are likely.

Literature. Findley and Jones 1967.

Fossil specimens often can be assigned to the genus, but cannot be identified to species.

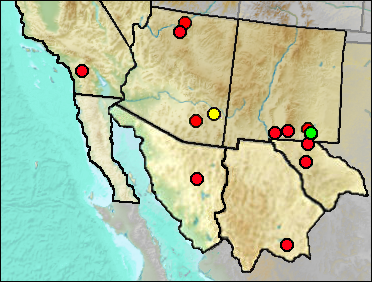

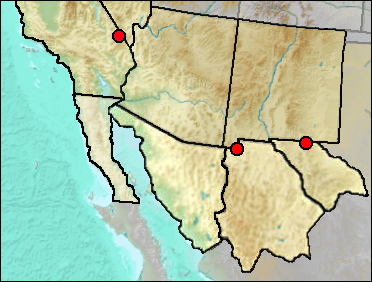

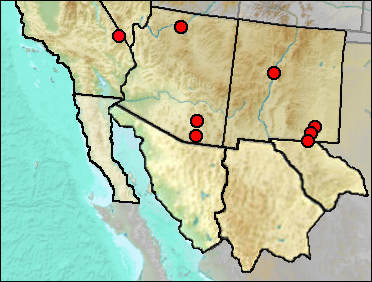

Sites.

Rancholabrean: Slaughter Canyon Cave (Morgan 2003).

Late Blancan: 111 Ranch (Morgan and White 2005).

Mid Wisconsin: Pendejo Cave (Harris 2003); Térapa (Czaplewski et al. 2014).

Mid/Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Bida Cave (Mead et al. 2005); Jimenez Cave (Messing 1986); Sierra Diablo Cave (UTEP).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Diamond Valley (Springer et al. 2009); Sandblast Cave (Emslie 1988: cf. gen.).

Late Wisconsin: Algerita Blossom Cave (Harris 1993c: cf.); Mystery Light Cave (this volume).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Carlsbad Caverns (Baker 1963); Conkling Cavern (UTEP); Deadman Cave (Mead et al. 1984: cf. genus); Stanton's Cave (Olsen and Olsen 1988).

Literature. Baker 1963; Czaplewski et al. 2014; Emslie 1988; Harris 1993c, 2003; Mead et al. 1984; Mead et al. 2005; Messing 1986; Morgan 2003; Morgan and White 2005; Olsen and Olsen 1988; Springer et al. 2009.

The most likely fossil species of Myotis describable as "small" are M. californicus and M. ciliolabrum. However, most identified specimens have not been measured, instead being identified as small on subjective criteria. Myotis yumanensis and M. lucifugus, for example, might be considered small by some workers.

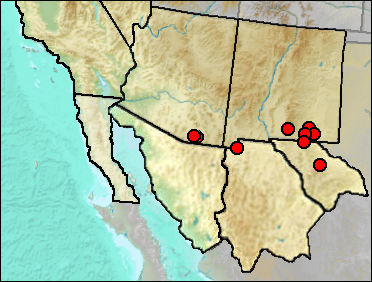

Sites.

Late Pleistocene: Arkenstone Cave (Czaplewski and Peachey 2003).

Mid Wisconsin: Papago Springs Cave (Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999).

Late Wisconsin: Animal Fair 18-20 ka (Harris 1989); Harris' Pocket (Harris 1989); Lower Sloth Cave (Logan 1983); U-Bar Cave 14-15 ka (Harris 1989); U-Bar Cave 15-18 ka (Harris 1989); U-Bar Cave 18-20 ka (Harris 1989).

Literature. Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999; Czaplewski and Peachey 2003; Harris 1989; Logan 1983.

Presumably such species the size of Myotis velifer or M. thysanodes are meant.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Antelope Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991).

This species and M. ciliolabrum are similar in size, and the identification of modern specimens frequently have been confused. The problems are compounded for osteological materials. The skull of M. californicus is more rounded, the rostrum narrower, and the coronoid process is lower (Gannon et al. 2001). The cranial area is seldomly preserved whole in fossils, but the other characters might be of use.

Both species are widespread in the West. Where allopatric, they both tend to be aerial hawking species, hunting "along margins of tree clumps, edges of tree canopy, over water, and well above ground in open country" (Gannon et al. 2001:78). Gannon et al. note, however, that M. ciliolabrum switches behavior when the two species are sympatric, becoming a gleaner and hunting near rocky bluffs. Identification of either of these does little in terms of revealing past environments.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Dry Cave 14-15 ka (Harris 1993c:?).

Literature. Gannon et al. 2001; Harris 1993c.

Synonyms. Myotis leibii, Myotis subulatus

See the discussion under M. californicus.

Sites.

Mid Wisconsin: Lower Sloth Cave (Logan 1983); U-Bar Cave (Harris 1993c).

Late Wisconsin: Antelope Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Kokoweef Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991).

Literature. Harris 1993c; Logan 1983; Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991; Reynolds, Reynolds, Bell, and Pitzer 1991.

Synonyms. Myotis leibii, Myotis subulatus

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Animal Fair (UTEP); Dust Cave (Harris and Hearst 2012); Pendejo Cave (UTEP).

Literature. Harris and Hearst 2012.

Myotis evotis is a gleaner commonly found in higher elevations in the Southwest. Presence suggests trees in the area.

Sites.

Rancholabrean: Papago Springs Cave (Skinner 1942: ? sp.).

Late Wisconsin: Harris' Pocket (Harris 1993c).

Literature. Harris 1993c; Skinner 1942.

Tebedge (1988) identified four elements from Dark Canyon Cave as M. lucifugus; three were edentulous dentaries and one a dentary fragment with m2-m3. In view of the number of possible species of about the same size, perhaps the identifications should be taken with a grain of salt, as likely should all other identifications of medium and small size Myotis. Also see the remarks under Myotis occultus.

Sites.

Mid Wisconsin: U-Bar Cave (Harris 1987: ?).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Dark Canyon Cave (Tebedge 1988).

Late Wisconsin: Bison Chamber (Harris 1993c); Harris' Pocket (Harris 1989).

Literature. Harris 1987, 1989, 1993c; Tebedge 1988.

Synonyms. Myotis lucifugus occultus.

There has been a great deal of confusion as to the relationship of M. occultus to M. lucifugus (summarized in Piaggio et al. 2002). Although described as separate species in the very early 1900s, morphological overlap in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico resulted in considering that overlap to represent intergradation between subspecies (Findley and Jones 1967, Barbour and Davis 1970). However, Hoffmeister (1986) found that in the region of overlap, there appeared to be two distinct groups with a few intermediates, and concluded that this tentatively warranted specific recognition. In a 1999 paper, Valdez et al. concluded on the basis of an allozyme analysis that there was little or no genetic differences between the populations, but that M. occultus be retained as a subspecies of M. lucifugus because of the morphological differences.

Piaggio et al. (2002) performed an examination of two mitochondrial genes, comparing samples of occultus from Colorado and New Mexico with M. lucifugus carissima from Wyoming (with one specimen from California). In their analysis, "occultus" separated out from M. l. carissima at a level consistent with the differences they found in the same study between M. yumanensis and M. velifer. The geographic area (southern Colorado and northern New Mexico) in the supposed zone of intergradation had characters more or less intermediate, but in their analysis consistently grouped with M. occultus. They conclude (p. 391-392) "that sufficient evidence exists to corroborate specific status for the taxa in our analysis...." These findings leave the paleontologist in somewhat of a quandary. Although such characters as the frequent reduction of the number of upper premolars and larger size may identify some fossils as M. occultus, specimens of M. occultus with characters such as seen in northern New Mexico would result in identification as M. lucifugus.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Fowlkes Cave (Dalquest and Stangl 1984b).

Myotis lucifugus

Literature. Barbour and Davis 1970; Dalquest and Stangl 1984b; Findley and Jones 1967; Hoffmeister 1986; Piaggio et al. 2002; Valdez et al. 1999.

Myotis rectidentis was described by Choate and Hall (1967) from Laubach Cave, Georgetown, Travis County, Texas, based on fossil material recovered by Bob Slaughter. A radiocarbon date on bone from Laubach Cave is 13,900 ± 400 BP, but was thought by Slaughter to be too young. The diagnosis (p. 532) is: "Large for the genus (crown-length of m1-m3, 3.70-4.05; crown-length of M1-M3, 4.45); c long (0.80-1.60) relative to length (also depth) of mandible, axis almost vertical; dorsal half of mandible flared outward; p2 crowded in depression between p1 and p3; mandible relatively thick ...". Choate and Hall also indicated that the nearest relatives were M. velifer and M. evotis.

In Fig. 1, comparison is made with the species thought by Choate and Hall (1967) to be those most closely related to M. rectidentis. Note especially the crowded premolars of UTEP 6-450, resulting in a notably short distance between the canine and the first molar.

Fig. 1. Modern dentaries of Myotis evotis (top) and M. velifer (bottom) compared with lateral and dorsal views of UTEP 6-450, tentatively identified as Myotis rectidentis. Scale is mm.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Bison Chamber (Harris 1989: cf.); Harris' Pocket (Harris 1989: cf.).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Beyond Bison Chamber (Harris 1993c: cf.).

Literature. Choate and Hall 1967; Harris 1989, 1993c.

This species is fairly common today from desert into lower forest.

This species is fairly common today from desert into lower forest.

Fig. 1. Ventral skull and dentaries of modern specimen of M. thysanodes. Myotis species look pretty much like this, with small differences in size and sometimes proportions of teeth.

Sites.

Late Pleistocene: Arkenstone Cave (Czaplewski and Peachey 2003).

Early/Early-Mid Wisconsin: Rm Vanishing Floor (Harris 1993c: ?).

Mid Wisconsin: Papago Springs Cave (Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Bida Cave (Mead et al. 2005).

Late Wisconsin: Lower Sloth Cave (Logan 1983); Muskox Cave (Logan 1981).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Isleta Cave No. 1 (UTEP); Kokoweef Cave (Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991).

Literature. Czaplewski and Peachey 2003; Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999; Harris 1993c; Jefferson 1991b; Logan 1981, 1983; Mead et al. 2005; Reynolds, Reynolds, et al. 1991.

Myotis velifer is the largest of our regional, present-day Myotis. Aside from the large size, presence of a sagittal crest will separate it from other regional species except M. occultus. Present distribution is primarily southern Southwestern and into Mexico, but it does extend east of our region into southern Kansas. It tends to be a waterway hunter, cruising up and down the Pecos River, for example.

Tebedge (1988) identified a number of elements of Myotis velifer from Dark Canyon Cave. He indicated that his specimens averaged smaller than those of Myotis magnamolaris, which he noted as the only larger species of Myotis in America. He apparently missed papers by Dorsey (1977) and by Dalquest and Stangl (1984a) that synonymized M. magnamolaris with M. velifer. Current populations of the latter in the Panhandle of Texas are nearly or quite as large as M. magnamolaris.

Identification of this species likely is relatively sound.

Sites.

Early/Early-Mid Wisconsin: Lost Valley (Harris 1993c); Rm Vanishing Floor (Harris 1993c).

Mid Wisconsin: Kartchner Cave (Buecher and Sidner 1999); Papago Springs Cave (Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999); U-Bar Cave (Harris 1987).

Mid/Late Wisconsin: Dark Canyon Cave (Tebedge 1988); Pendejo Cave (UTEP).

Late Wisconsin: Animal Fair 18-20 ka (Harris 1989: cf.); Bison Chamber (Harris 1989: cf.); Harris' Pocket (Harris 1989); Lower Sloth Cave (Logan 1983); Muskox Cave (Logan 1981); TT II ( (Harris 1993c: cf.); U-Bar Cave 13-14 ka (Harris 1989: cf.); U-Bar Cave 14-15 ka (Harris 1989: cf.); U-Bar Cave 15-18 ka (Harris 1989); U-Bar Cave 18-20 ka (Harris 1989: cf.); Upper Sloth Cave (Logan and Black 1979).

Late Wisconsin/Holocene: Balcony Room (Harris 1993c); Beyond Bison Chamber (Harris 1993c); Fowlkes Cave (Dalquest and Stangl 1984b).

Literature. Buecher and Sidner 1999; Czaplewski and Mead et al. 1999; Dalquest and Stangl 1984a, 1984b; Dorsey 1977; Harris 1987, 1989, 1993c; Logan 1981, 1983; Logan and Black 1979; Tebedge 1988.

Synonyms. Pipistrellus hesperus.

This small bat occurs throughout our region in lower elevations up to woodland habitats. They often are found in foothill situations where rocky cliffs supply crevices for day use.

Sites.

Late Wisconsin: Skull Cave (Emslie 1988).

Literature.

Last Update: 7 Oct 2019