UTEP Geological Sciences Team to Study Receding Antarctic Glacier

Last Updated on May 02, 2018 at 9:00 AM

Originally published May 02, 2018

By UC Staff

UTEP Communications

Researchers from The University of Texas at El Paso’s Department of Geological Sciences are part of an international team participating in a multimillion-dollar, joint research program between the United States and the United Kingdom that seeks to understand how quickly a massive Antarctic glacier could collapse.

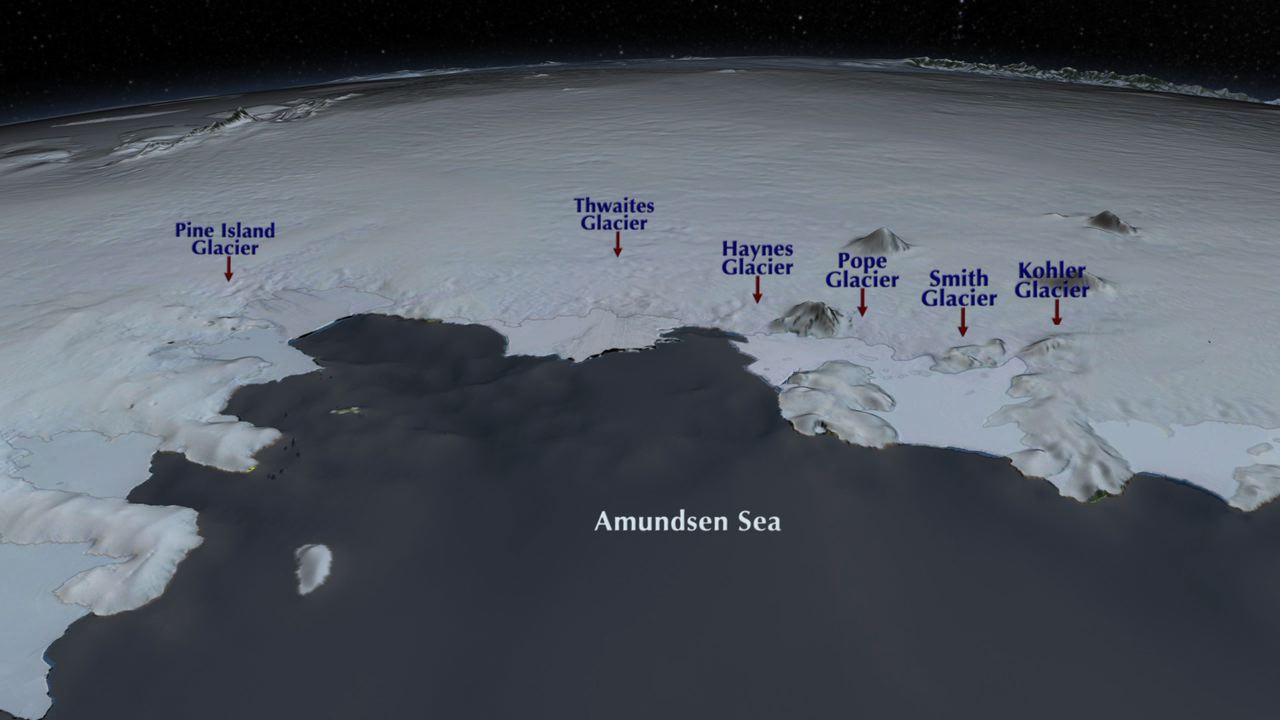

Marianne Karplus, Ph.D., Steven Harder, Ph.D., and Galen Kaip will participate in the Thwaites Interdisciplinary Margin Evolution (TIME) project. They will use precision seismic, GPS and radar instrumentation to collect new data on the current behavior and future evolution of Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica. These new data will help improve computer models used to predict the future contribution of the West Antarctic ice sheet to global sea level changes. The five-year project will begin in October 2018.

“Understanding the structure and dynamics of the shear margins of Thwaites Glacier will allow us to better understand how rapidly ice flows from the Antarctic ice sheet into the ocean,” Karplus said. “Through this international research effort, we will collect new data that will improve predictions of future sea level changes. I am excited to investigate these important scientific questions with this group of highly skilled interdisciplinary scientists in one of the most remote locations on Earth.”

Thwaites Glacier has been called the “weak underbelly” of the West Antarctic ice sheet because of its potential to abruptly increase the amount of ice flowing into the ocean, significantly affecting global sea levels.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.K. Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) are launching the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), a $25 million initiative supporting the efforts of about 100 scientists working on eight different research projects to help predict the future evolution of Thwaites Glacier and assess the sensitivity of the Antarctic ice sheet to changes in climate. The TIME project is one of those eight research projects.

The UTEP Seismic Source Facility, led by Harder and Kaip, has supported seismic imaging projects around the globe, including in Antarctica, Greenland and Alaska. Karplus has led seismic imaging projects on a temperate glacier in Alaska and at remote field sites in the Himalayas and Tibet, but this will be her first time working in Antarctica. The UTEP team will contribute to high- resolution seismic imaging intended to identify sediments, fluids and other geologic structures that influence glacial dynamics. This information can then be used in numerical modeling to forecast movement with time.

The TIME project has received $3.4 million in funding, including $2.4 million from NSF for the U.S. investigators and $1 million from NERC for the U.K. investigators. The TIME project is co-led by Slawek Tulaczyk, Ph.D, professor of physical and biological sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Poul Christoffersen, Ph.D., senior lecturer at the University of Cambridge Centre for Climate Science. The project also includes six other researchers from the University of Oklahoma, Stanford University, the University of Leeds and the University of Cambridge.

While researchers on the ice will rely on aircraft support from U.K. and U.S. research stations, oceanographers and geophysicists will approach the glacier from the sea in U.K. and U.S. research icebreakers.

“For more than a decade, satellites have identified this area as a region of massive ice loss and rapid change. But there are still many aspects of the ice and ocean that cannot be determined from space,” said Ted Scambos of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, the lead U.S. scientific coordinator of ITGC. “We need to go there, with a robust scientific plan of activity, and learn more about how this area is changing in detail, so we can reduce the uncertainty of what might happen in the future.”