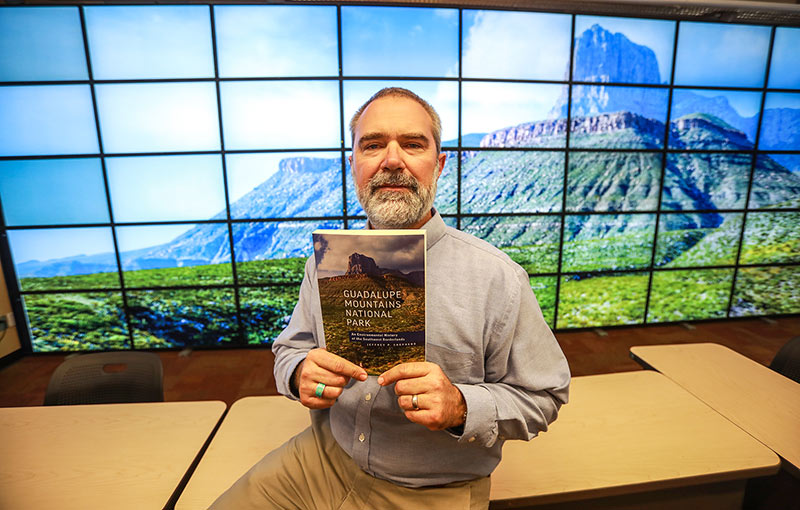

UTEP Professor's Book Promotes Guadalupe Mountains

Last Updated on October 28, 2019 at 12:00 AM

Originally published October 28, 2019

By Daniel Perez

UTEP Communications

As long as he can remember, Jeffrey Shepherd has loved the outdoors. The native of Jacksonville, Florida, treasured his opportunities to camp, fish and hike or bike on public lands. He especially was fond of national parks, which were among his favorite places to relax.

“To be out in nature at the parks calms the soul,” said Shepherd, Ph.D., associate professor of history at The University of Texas at El Paso.

Shepherd has visited dozens of national parks across the country, and some of those stopovers led to his interests in environmental history, Western U.S. history and Native American history, especially about the Apaches. The National Parks Service (NPS) decided in 2007 that his expertise made him the perfect candidate to prepare a historical resource survey of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park, about 90 minutes northeast of El Paso.

The NPS awarded the UTEP professor a two-year, $80,000 grant to study the area from prehistoric times through its establishment as a national park in 1966. Because of the depth and breadth of his research, Shepherd said he knew he had the material to write a book about the history of the Guadalupe Mountains and their unique geological formations such as the exposed barrier reef – the largest one in the world – and El Capitan, the highest point in Texas at 8,749 feet. The mountain range, surrounded by the Chihuahuan Desert and salt flats, is a popular destination for astronomers and geological researchers. More than 1,000 species of plants and trees to include some that are unique to the area top the range.

Despite his interest in the subject and the desire to write the book, other obligations kept him from the project until about three years ago. Shepherd said he hoped that his “Guadalupe Mountains National Park: An Environmental History of the Southwest Borderlands,” published by University of Massachusetts Press in June 2019, would make readers more appreciative of the region, its history and how humans learned to make do with the available natural resources. He plans to discuss his book at 10 a.m. Saturday, Nov. 2, 2019, at the El Paso County Historical Society, 603 W. Yandell Dr.

“They are what the people in the parks service call our national heritage,” Shepherd said. “It’s what we can bequeath to our children. That’s the personal part for me. I want society to value these national parks. They are public places for all people. We all deserve access to these parks.”

The U.S. government created the National Parks Service in 1916. Through 2019, Congress established 61 national parks with two of them in Texas. The other is Big Bend National Park in Southwest Texas, which the government approved in 1944.

Shepherd based his 280-page book on the NPS report that he delivered in 2012. The U.S. government uses these reports to assist the NPS with their tours, literature, management of cultural resources and educational programming. He conducted additional research after he submitted his report to add a chapter to his book that brings the park’s history to the present.

The UTEP educator found most of the relevant archives – primary source documents, government reports, military maps and records, as well as records from Indian affairs, etc. – in university libraries in Texas and New Mexico. He also made the difficult hike to the top of the range twice as part of his research for the book.

Shepherd’s willingness to go into the field to suggest and exchange ideas on how to preserve and protect the park’s resources helped build trust and rapport with the park staff, remembered Bob Spude, Ph.D., former regional historian for the NPS intermountain region based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, during the project. He retired in 2012 after 35 years with the NPS.

Spude (pronounced SPOO-dee) gave equal credit to the park staff members who helped Shepherd to ferret out every detail from the park’s files. He praised the academic outdoorsman as a skilled researcher whose work went beyond the original contract. The retired historian said he was ecstatic with the book.

“Too often we forget the human story in such great natural parks as the Guadalupe Mountains,” Spude said. “(Shepherd) has accomplished what I had hoped for – a rich, detailed narrative that will help the general public understand the many stories within this parkland and its environment.”

Shepherd said he spent about 15 percent of his estimated three years of research time in the Texas General Land Office in Austin, Texas. He reviewed the deeds and discovered how two individuals – J.C. Hunter Jr., and Wallace Pratt – started to buy much of the land in the 1920s. Hunter amassed about 62,000 acres and turned it into a ranch. Pratt, a wealthy petroleum geologist for Standard Oil, bought 17,000 acres for his retirement. He initially built a cabin and later a huge house, but otherwise left the land intact.

“That was a lot of grueling work,” Shepherd said with a laugh and then repeated himself for emphasis. “Really grueling work, but it was a rich source of information.”

The UTEP professor said both families decided in the early 1960s that they wanted to donate or sell off their land to create a park. That idea interested some powerful people in government to include U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough, D-Texas, and U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas. Yarborough was an outdoorsman and Douglas was an environmentalist. Both were familiar with the Guadalupe Mountains. These influential individuals had the assistance of local groups such as the El Paso Chamber of Commerce and the El Paso branch of the Sierra Club. Editorials from newspapers in Texas and New Mexico also cultivated regional support for the bills moving through Congress. The initial bills to create the Guadalupe Mountains National Park emerged in 1964, but most politicians ignored them as they spent most of their time in debates about Vietnam and the civil rights movement. Their biggest concern was how to buy the land, which was private property. The answer was the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965, which established a fund to buy land to meet the present and future outdoor recreation demands of the American people. The Guadalupe Mountains National Park was the first national park paid for with federal funds. The government used private donations to pay for previous national parks that were not on federal land.

Pratt eventually donated his land. Hunter willingly sold his land for pennies on the dollar. Legislators approved the national park in less than five years. Shepherd said such deals could take up to 25 years. He said some factors in its favor was that it had the support of Yarborough and President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Texan, and the fact that the land did not have any oil, natural gas or valuable mineral deposits.

Shepherd also learned a lot about the park’s creation at the Texas Tech University Special Collections Library in Lubbock. He spent about four weeks there in 2011 reviewing papers of people involved in the park’s history, said Monte Monroe, Ph.D. state historian of Texas and archivist for the library’s Southwest Collection.

Monroe praised Shepherd as a highly regarded researcher of which UTEP should be proud. He also commended the book for its insights into environmentalism and the early conservation movement.

“This is a story that needed to be told,” Monroe said. “The book is a great study built on solid scholarship.”

Shepherd said that part of the reason he wrote the book was out of respect for the park service, which chronically is underfunded and under pressure from climate disruption (fires and floods) and people who want to privatize public lands.

The challenges they face in states such as Texas are considerable because there is very little public land in Texas.

“A national park in Texas is a very special place,” he said.