Bhutan

UTEP's relationship with Bhutan began with architecture in 1917 and has extended to include foreign students, festivals, and an international opera performance as part of the Centennial Celebration.

About Bhutan

Bhutan is a Himalayan kingdom located along the northeast frontier of India, just above Bangladesh. It is a landlocked country, sharing a 605 km. border with India and an undefined 470 km. border with China to the north. Bhutan’s land area is roughly the size of the combined states of Massachusetts and Connecticut (14,824 square miles; 38,394 sq. km.) with a population of over 700,000. Following the ratification of its constitution in 2007, the government of Bhutan established itself as a constitutional monarchy with a bicameral parliament. Its civil law is based on Buddhist religious law, with more than 75 percent of the nation practicing Buddhism and the remainder adhering to Hinduism.

As a landlocked nation, Bhutan’s first diplomatic contact with major world powers did not occur until the mid-1800s. In 1865, Bhutan settled a border dispute with British India (the Treaty of Sinchulu) and agreed to cede land to India in return for annual financial aid. In 1907, Britain assisted the nation in establishing a stable monarchy, with British India handling its foreign affairs. India, following its independence from Britain in 1947, assumed this role and to this day still coordinates Bhutan’s foreign policy. Bhutan celebrates its founding as a nation on December 17 (National Day). Its national anthem is Druk tsendhen (The Thunder Dragon Kingdom).

Given its mountainous terrain, less than three percent of Bhutan is arable land suitable for agriculture. However, the Himalayas provide an abundance of timber, gypsum, as well as being a source of hydroelectric power. Its location along the Himalayas makes it susceptible to the region’s violent thunderstorms, and contributes to Bhutan’s reputation as the Land of the Thunder Dragon.

Campus Architecture

UTEP's campus is known for its striking architecture, inspired by the Himalayan mountain-top fortresses of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Nearly all of the buildings on campus incorporate Bhutanese architectural elements—massive sloping walls, high inset windows, overhanging roofs, and darks bands of brick inset with mosaic-tiled mandalas. The buildings, like fortresses rise out of the mountain landscape. The earthly colors accented with deep red brick and green and dark brown trim seem to blend into the terrain, yet they do not evoke the typical southwestern motif. At first brush, it might seem strange to find Bhutanese architecture sprawling across a university campus in western Texas, but the style has been a part of the campus design since 1917.

Bhutan’s remoteness and self-imposed isolation kept it off of the beaten tracks of most tourists and adventurers until the late 20th century. However, those involved with the administration of British India did visit the kingdom on official business. John Claude White, a British political officer in India, took with him on one of his visits a photographic studio complete with large-format cameras and glass photographic plates carried on the backs of pack animals. The tale of his trip along with the photographs made it into the pages of the National Geographic Magazine’s April 1914 issue. Among the many images were those of the countries unique architecture.

One of the 330,000 readers to the National Geographic Magazine in 1914 was the wife of the dean of the School of Mines, Kathleen Worrell. A travel writer herself, Kathleen was devoted reader of the flagship travelogue. Following the devastating Fort Bliss fire that destroyed the School of Mines’ original main building, Kathleen, the legend goes, convinced her husband to adopt the Bhutanese style in the designs for the replacement buildings that were planned for the new Franklin Mountain site. Her husband, Dean Steve Worrell agreed and promptly convinced the faculty of the idea. So enamored were they that Worrell and the faculty harshly rebuffed an attempt by the noted architectural firm of Trost & Trost to adopt their non-Bhutanese inspired design submissions.

In the late 1960s, Dale Walker, a UTEP faculty member wrote a letter that he sent to the remote and isolated Kingdom of Bhutan, seeking comments on UTEP’s Bhutanese-inspired architectural motif. Walker received a response from a member of the Bhutanese royal family who found it “thrilling and deeply moving” that a university in far-off America would erect buildings modeled on her native Bhutan. Thus began an official relationship between UTEP and the Kingdom of Bhutan, fifty years after the Worrells adopted Bhutan.

Students from Bhutan

Dale Walker’s first contact with the Bhutanese royal family began a close relationship between UTEP and Bhutan that endures to this day. One of the immediate aftermaths was the arrival and enrollment of Jigme Dorji at UTEP. Jigme, known as Jimmy to his classmates, studied engineering at the school, graduating in 1978.

Since Jigme Dorji's graduation, many Bhutanese natives have traveled the 8248 air nautical miles between Bhutan and El Paso to study at UTEP. Their majors have included engineering, finance, accounting, geophysics, and education.

Bhutan Connections

Many connections to Bhutan can be found on campus in a wide variety of artifacts. Many of these artifacts were highlighted in Bhutan Days celebration, first held in 2005.

Handcrafted Altar

University Communications

A masterpiece of Bhutanese craftsmanship is on display in the University Library atrium.

The elaborately carved Bhutanese altar, hand painted with birds, serpents and flowers, stands 8 feet tall and 23 feet long. It was donated to UTEP by the Asia Society after an exhibit in New York.

The altar’s deep, rich colors have special religious significance in Bhutan. Its windows, framed by fanciful carved and painted woodwork, are meant to reflect light from butter lamps left as offerings to the gods.

Symbols of Learning

Just above the altar in the Library atrium hangs a magnificent hand-embroidered tapestry.

Made by Buddhist monks in Bhutan’s capital of Thimphu, the 12-by-16 foot tapestry was commissioned by the university in 1987. It incorporates dragons and other powerful symbols traditionally found in Bhutanese culture.

A decade later, the university commissioned the 18-by-24 foot tapestry that now adorns the Undergraduate Learning Center’s first floor. Hand embroidered by Bhutanese monks, this tapestry features symbols of education and worldly fortune.

In Bhutan, huge tapestries like these are hung from dzongs during Buddhist festivals to confer blessings on the assembled faithful.

Spicy Traditions

Traditional Bhutanese food features spicy red or green chiles. A traditional dish called emadatsi is made of green chiles prepared with a cheese sauce, much like the chile con queso so popular in the American Southwest. This zesty dish is mirrored in the Centennial Salsa products made available as part of UTEP's Centennial Celebration.

Another popular dish is vegetable curry with rice. More remote villages also specialize in tsampa, a Tibetan-style dish of barley flour mixed with salt and butter tea, then kneaded into paste.

Goodwill and Peace

An authentic Buddhist prayer wheel handcrafted in Bhutan is located in the gardens of the Centennial Museum.

The large cylindrical vessel is filled with handwritten prayers of goodwill. When spun in a clockwise direction, it is said to send out messages and blessings of peace.

The lawn of the museum is decorated with multi-colored prayer flags. As they flutter in the breeze, they are believed to lift prayers to the heavens.

Biggest Book in the World

in the University Library, 2005

University Communications

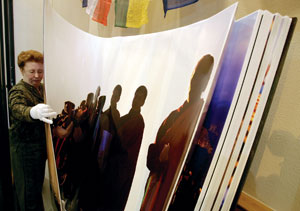

Weighing 133 pounds and measuring 5-by-7 feet, Bhutan: A Visual Odyssey Across the Last Himalayan Kingdom is certified by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s largest published book.

The 114-page tome, which was donated to UTEP, is on permanent display at the University Library. It’s listed as UTEP’s one-millionth volume.

Portraits of people are life-size, or bigger. Panoramas convey some of the staggering sweep of the Himalayans and the graceful Bhutanese architecture.

Opera Bhutan

Opera Bhutan: Acis and Galatea is an unprecedented international production that unites performers from around the world in a once-in-a-lifetime performance that incorporates elements of song, dance, instrumentation and visual arts from Western opera and eastern musical storytelling of the Kingdom of Bhutan.

Acis and Galatea

George Frideric Handel’s opera Acis and Galatea is a love story from Greek Mythology that emphasizes love and virtue, tragedy and transformation, transcendence and triumph. This setting of the opera is the first opera in the world to incorporate Bhutanese dance and cultural elements to create a brand new form of expression. Opera is a foreign concept to the Bhutanese people, who have remained geographically and culturally isolated from the rest of the world until very recently. In 1999, Bhutan became the last country in the world to legalize television. Read about this world premiere performance on the Centennial Blog.

Opera Bhutan

Opera Bhutan unites UTEP students, faculty, and staff with Bhutanese dancers as well as artists from around the world, including Italy, Cameroon, Canada, Australia and the United States. It is a collaboration between The University of Texas at El Paso, the El Paso Opera, the Royal Government of Bhutan, Bhutan’s Royal Academy of Performing Arts, and Bhutan’s Royal Textile Academy. The Opera Bhutan project originated in the mind of Aaron Carpenè, a musician and conductor who contacted Preston Scott, adviser to the Royal Government of Bhutan on a range of cultural projects, in 2004 to ask if an opera had ever been performed in the country. The answer was no, but the timing was not right for the Bhutanese government to pursue it.

By 2010, the project had evolved to include Italian stage director Stefano Vizioli and UTEP. Three years later, a group of about 70 people from 10 countries were in Bhutan preparing to perform the opera.

At the first rehearsal in Thimphu, the UTEP team was greeted by a dozen other foreigners working on the project who had already been in the country for a few days, as well as Bhutanese dancers, musicians, carpenters and painters. Karma Wangchuk led the Bhutanese construction crew. He is the architect who has consulted with UTEP on the lhakhang, a Bhutanese building constructed for the Smithsonian Folklife Festival that was donated to the people of the United States and resides on the UTEP campus as a cultural center.

Wangchuk and his team, along with technical directors and audio engineers from the Smithsonian, were busy constructing a wooden stage and tents in the courtyard of Thimphu’s Royal Textile Academy. Since performances on a stage with an orchestra were unknown in Bhutan, the Opera Bhutan crew had to construct everything, from speaker and monitor stands to orchestra risers and music stands.

The instrumentalists and singers knew their music before arriving in Thimphu, as did the four lead vocalists – Francesca Lombardi Mazzulli (Italy), Thomas Macleay (Canada), Jacques-Greg Belobo (Cameroon) and Brian Downen (United States) – but no one knew the choreography and staging until those last two weeks of preparation in Bhutan with Vizioli.